SummaryWith markets now expecting US interest rate cuts as soon as August, we’re often asked whether it is realistic for the ECB and BoE to continue to hike rates in the months ahead. Assuming our view on US interest rates is correct, and the Fed remains on hold through the rest of 2023, we believe the answer to this question is clearly yes, and that this is likely to result in a period of outperformance for US Treasuries relative to comparable bunds and gilts.

|

Can European central banks keep hiking?

The Fed have paused their hiking cycle

Following one of the most aggressive periods of monetary tightening in recent history, Fed chair Jerome Powell softened his language in the press conference that followed the May meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). This makes it likely that the post meeting range of 5% to 5.25% for Fed Funds represents the peak for US interest rates in this current tightening cycle. After the press conference, markets moved to anticipate not just the end of the hiking cycle, but to price in rate cuts later in 2023. In Europe, however, central banks continue to strike a more hawkish tone. The ECB, having raised its deposit rate to 3.25%, continue to indicate at least two more interest rate hikes to come, and in the UK, the Bank of England (BoE) are expected to edge interest rates upwards from 4.5%.

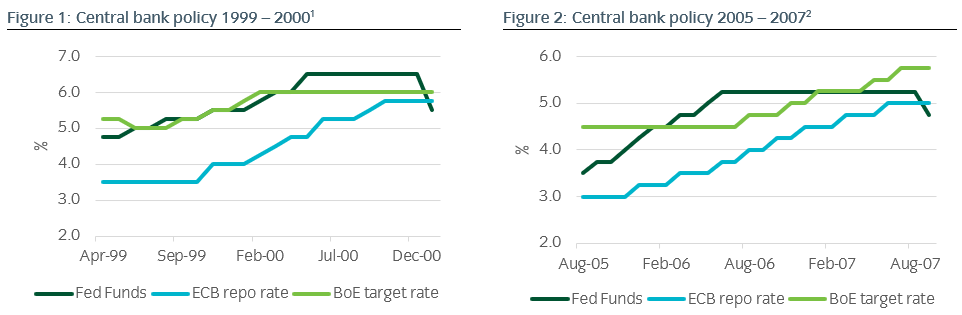

European rate hikes have often continued after a Fed pause

Although it may appear unusual at first glance, it is actually relatively normal historically for European interest rate cycles to lag US interest rate cycles, and for interest rate hikes to continue after the US hiking cycle has ended. For example, the Fed paused their hiking cycle in May 2000, but the ECB went on to hike a further three times over the following five months (see Figure 1). In 2006, the Fed paused their hiking cycle in June, but the ECB hiked a further five times over the following year, with the BoE hiking by the same amount over a 13-month period (see Figure 2).

1Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 30 April 1999 and 31 January 2001.

2Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 31 August 2005 and 30 September 2007.

The trigger for the start of US easing cycles usually has global implications

Although it’s not unusual for US rates to plateau well before European tightening cycles end, it is far more unusual for US and European interest rate cycles to completely diverge. The reason for this is simple – US rate cuts are usually a reaction to something breaking in the global economy, and this generally has implications for European central banks as well. At this stage, we don’t see anything sufficiently concerning to force the Fed’s hand. Although the collapse of confidence in several US regional banks has impacted sentiment across the global banking sector, ultimately forcing Swiss regulators to incentivise a takeover of Credit Suisse, the problem still appears non-systemic for now. This leaves us in disagreement with market pricing, and we believe the Fed will remain on hold into 2024.

There is still more work to be done in Europe

The reason European central banks remain under pressure is clear – inflation

In Europe, although energy prices are past their peak, and headline rates of inflation are falling, central banks remain concerned about the stickiness of inflation. More persistent inflationary pressures increase the risk of second-round effects, putting upward pressure on wages and risking that inflation expectations potentially become un-anchored. When we examine trends in core inflation on either side of the Atlantic, the reasons for these concerns become immediately apparent:

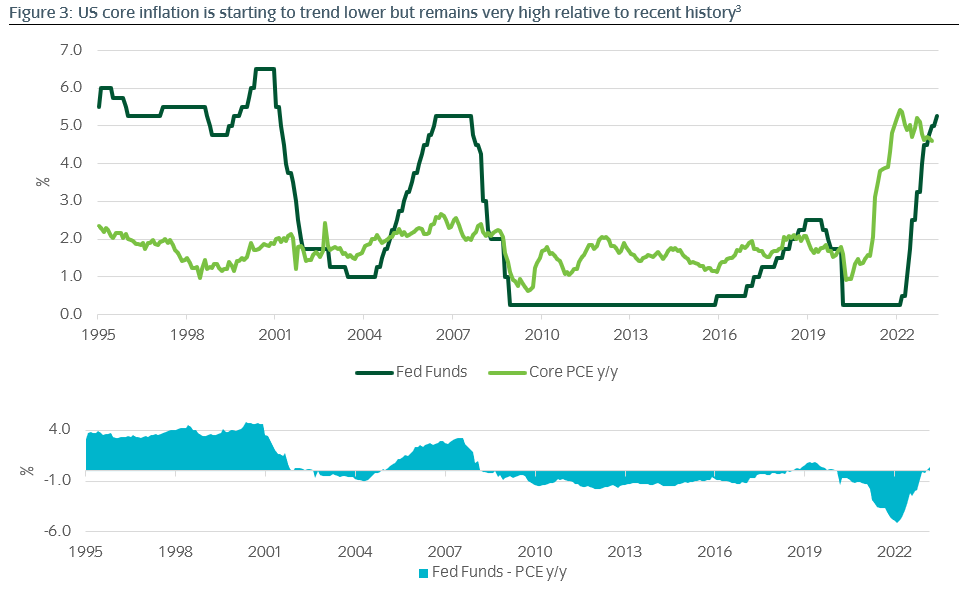

- In the US, core inflation has clearly passed its peak and started to trend lower. The FOMC have also raised interest rates to a level in excess of core PCE (the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index) is the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation), which suggests that sufficient action has been taken to sustain the downward trend (see Figure 3). That said, core inflation still remains well above the levels seen in recent decades, which is one reason why we believe the Fed will be far more reluctant to cut rates than market pricing would suggest.

3Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 31 Jan 1995 and 17 May 2023.

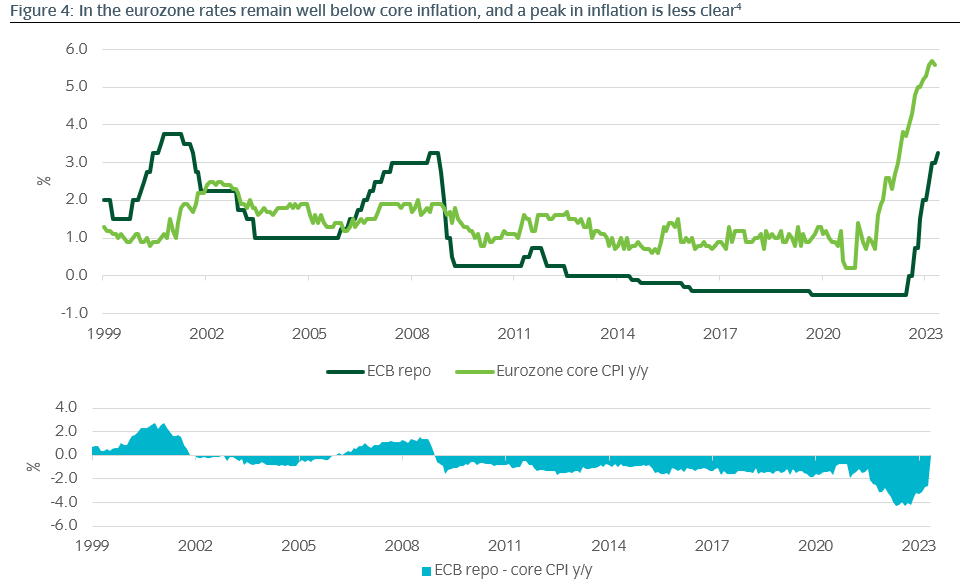

- This is not the case in the Eurozone. Although core CPI is expected to fall in the months ahead, there is still no clear sign of a peak and real ECB deposit rates remain deeply negative. ECB policy is simply not restrictive in the same way as Fed policy is.

4Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 31 Jan 1999 and 17 May 2023.

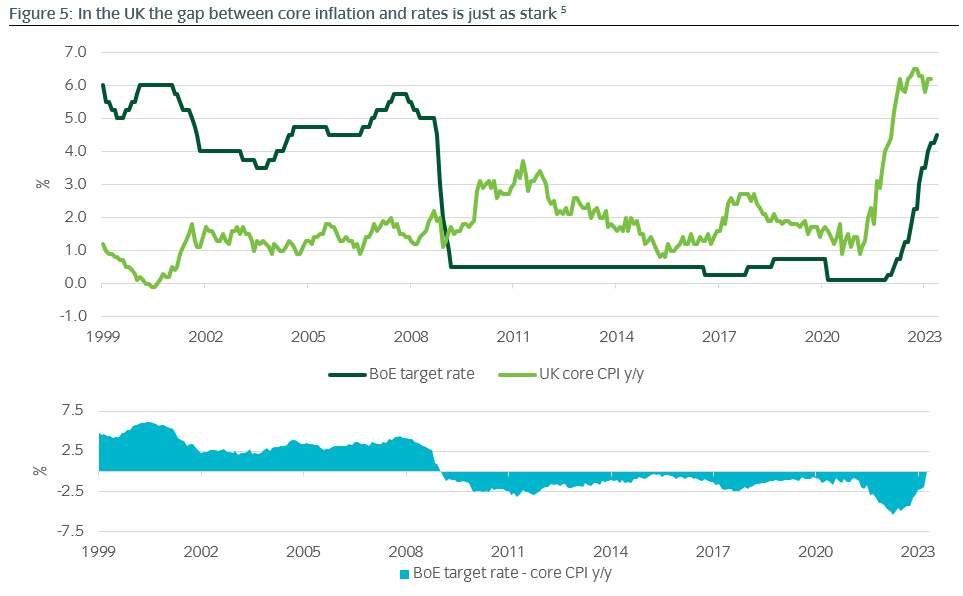

- In the UK, although there are arguably some signs that core CPI is rolling over, the trend remains unclear and UK rates are also still well below core inflation.

5Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 31 Jan 1995 and 17 May 2023.

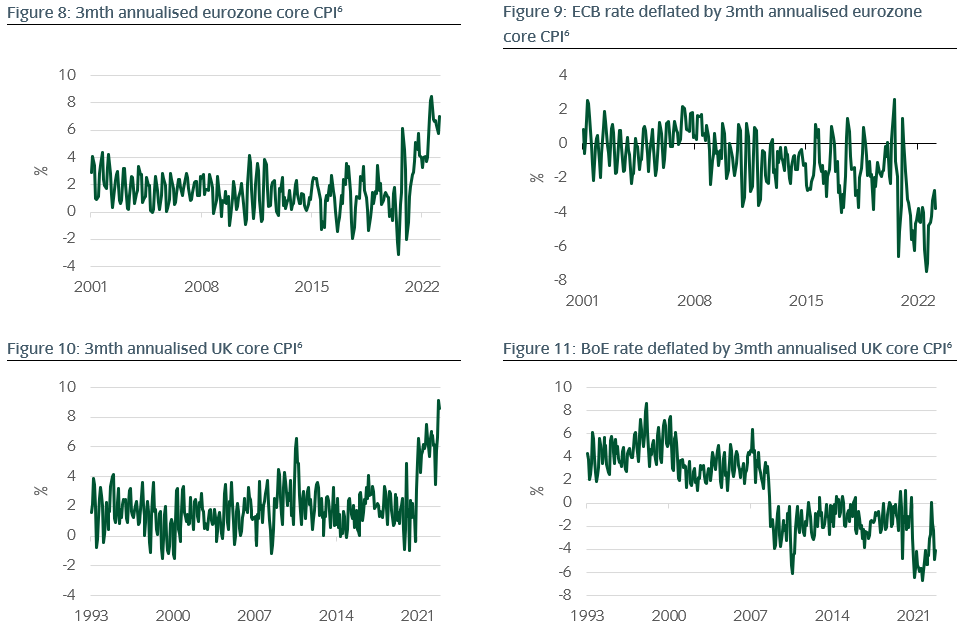

Shorter-term trends will provide little comfort to the ECB and BoE

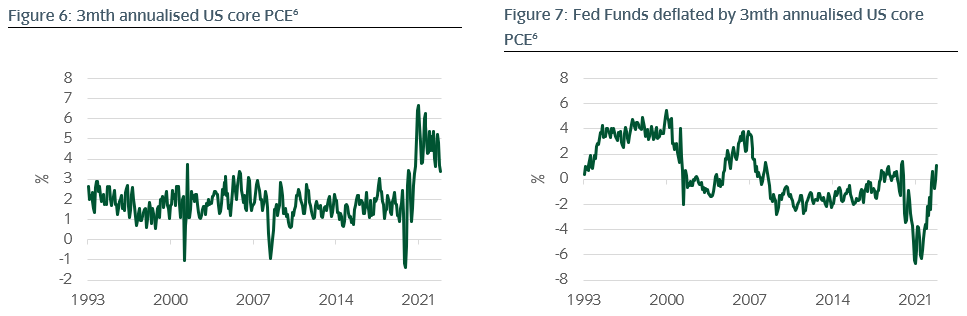

To investigate this further, we can examine shorter-term trends in core inflation to determine whether this divergence is a genuine concern. Using annualised three-month core CPI we can see a similar story as apparent in the longer-term data.

In both Euro and UK there seems to be something causing a rebound in the 3m annualised core inflation numbers, though this could be an effect of changing seasonals. It is notable that there is a bigger real rate gap in the euro area than UK using three-month annualised core CPI.

6Source: Insight and Bloomberg. Data between 31 Jan 2000 and 17 May 2023.

Conclusion

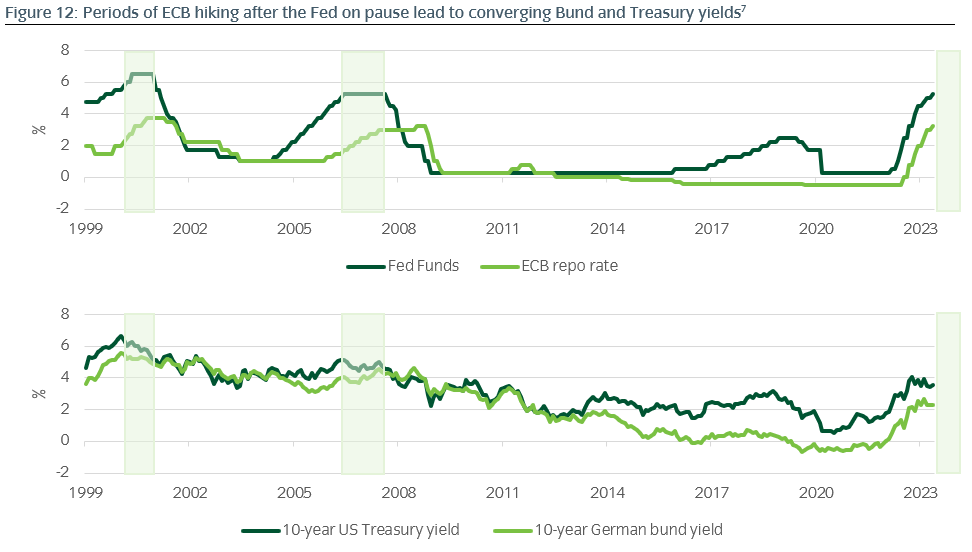

Having established that the hiking cycle in Europe can continue despite the Fed’s pause, the obvious next question is what the market implications are. As we can see in Figure 12, generally speaking, a Fed pause has provided a good indication that US Treasury yields are also at or close to a peak. But this is not always the case for bunds or gilts, which can continue to take direction from domestic central bank action. Given this, the strongest conclusion we can draw is not directional, but instead cross-market. In our view, this outlook means there is the potential for US Treasuries to outperform bunds, and perhaps also gilts, for the next several months ahead.