Shifting demand is forcing a change of strategy

In the revision to the DMO's financing remit for 2025/26, released after the budget, the DMO noted that it intends to launch a consultation in January 2026 regarding 'expanding and deepening the Treasury bill market'. The DMO went on to note that 'any changes following the consultation will take into account an assessment of cost and risk, including implications for the government’s refinancing risk exposure'.

Historically, defined benefit pension schemes were a key source of demand for gilts, favouring very long maturities to hedge long-term liabilities. As these schemes have become fully funded – and many are now in surplus – their need for new long-dated issuance has fallen sharply. This has left the DMO seeking alternative buyers, many of whom prefer shorter-dated bonds.

New sources of demand are potentially emerging. For example, higher interest rates have driven rapid growth in money market funds (MMFs). At the same time, corporates are actively managing their debt profiles and often hold large cash balances for extended periods, especially when refinancing their debts. These investors typically favour shorter maturities as they don't want to risk capital losses.

Beyond the traditional demand from Banks and money market funds, stablecoins could be a new source of future demand – which also links to the UK's ambitions to be at the forefront of the digital economy. Stablecoins are digital currencies, typically backed by short-term assets, that facilitate the transaction of digital assets, and are likely to become a critical part of the economy as the digitalisation of assets grows in popularity.

The Bank of England issued a consultation paper in November on the proposed regulatory regime for sterling-denominated stablecoins and proposed that under normal circumstances, sterling stablecoins should be 60% backed by short-term sterling-denominated UK government debt securities. Stablecoins recognised by HMT, and deemed systematically important, would be required to hold 95% of their assets in short-term sterling-denominated UK government debt, with the percentage declining to 60% as their scale in size.

Balancing cost savings with refinancing risk

The US Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) issued a paper in July 2024 titled 'Considerations for T-bill issuance' which notes that 'T-bills are a useful tool to achieve Treasury’s goal of funding the government at the lowest cost to the taxpayer over time'. However, the TBAC also note that 'substantially increasing the share of T-bills outstanding increases the volatility of deficit financing'. The TBAC conclude that a 'T-bill share averaging around 20% over time appears to provide a good trade-off between cost and volatility'.

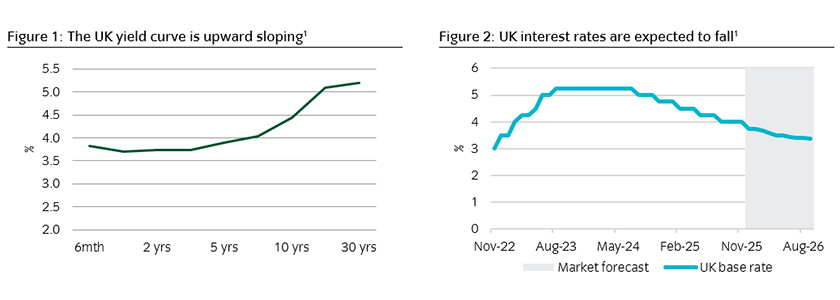

The DMO have likely drawn a similar conclusion and will be looking to take advantage of cheaper short-term borrowing costs (see Figure 1), which will become even more compelling if the Bank of England reduce interest rates as expected in 2026 (see Figure 2).

The UK has traditionally maintained a longer maturity profile than other major markets with a far lower level of short-term issuance than other developed economies. Although the DMO already issue Treasury bills, they are used for cash management purposes, rather than budget financing. According to the Debt Management Report 2025–26, outstanding Treasury bill issuance was £70.5bn at the end of 2024, or 3% of total outstanding UK government debt. This is well below the optimal 20% level outlined by the TBAC.

Increasing the issuance of Treasury bills is not without risk. As these issues are by their nature less than one year in maturity it means that the government has to constantly reissue maturing debt at the prevailing market rate. If short-term interest rates are increasingly rapidly, as we saw in 2022, then this can quickly push up the interest rate the government needs to pay to issue Treasury bills. This can make it more difficult for the government and OBR to predict future borrowing costs for the purpose of forecasting government budgets. In an extreme scenario, where investors shift away from UK assets due to some kind of crisis, rolling over large amounts of short-term debt could become difficult and might require central bank support.

On the other hand, issuing more Treasury bills could relieve the burden of issuance on the gilt market. Gilt issuance is already expected to decline as the UK budget deficit narrows, and a contribution from T-bills to the annual financing requirement would see this reduce further.

One ongoing challenge for the UK is that gilt yields trade at a premium to other major markets, creating a perception of higher risk. If reducing gilt supply narrows this gap, it could strengthen confidence in UK public finances.

Impact on markets

- MMFs: a larger and deeper Treasury bills market means more investable assets. UK money market funds, especially Public Debt CNAV and LVNAV structures, will have greater access to high-quality short-term instruments, which can help to improve portfolio liquidity and provide yield stability.

- Banks: increased Treasury bill issuance expands the pool of high-quality liquid assets. Banks can use these bills for repo transactions and regulatory liquidity buffers, improving short-term funding flexibility.

- Repo markets: with more Treasury bills in circulation, repo market dynamics depend on where those bills are held. If MMFs absorb most of the supply, their reduced cash lending could tighten repo liquidity. Conversely, if banks hold more bills, collateral availability for repo could increase.

The Bank for International Settlements published a working paper in May 2023: 'Money Market Funds and the Pricing of Near-Money Assets' which explored the interplay between these three in the US. The authors found that in the US, MMFs hold substantial T-bill holdings, and the market provides a useful source of supply when interest rates are high and MMFs typically receive large inflows.

During times of stress, money market funds (MMFs) can dramatically increase their holdings of T-bills – for example, exceeding $1 trillion during the early pandemic. When MMFs shift more cash into T-bills, they have less available for repo lending, which pushes repo rates higher. This raises bank funding costs and tightens credit conditions at precisely the time central banks usually want to ease them. It complicates the central bank’s response, but the impact can be mitigated by providing additional liquidity to banks.