|

| Gareth Colesmith, Head of Global Macro Research |

- French Prime Minister François Bayrou has called a confidence vote for 8 September 2025.

- Fresh legislative elections are likely in the autumn, but weak or divided government is the most probable outcome in any case.

- There is a high probability that a credit ratings agency downgrades France to A+.

- French political deadlock and fiscal deterioration will likely continue at least into the next presidential election, due in 2027. French government bonds and other French assets are likely to continue to underperform.

“Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose” is a French saying meaning that the more things appear to change, the more they stay the same. We have a fine example of that in French politics currently, with Prime Minister Bayrou calling a confidence vote in parliament over his proposed budget consolidation, reminiscent of former Prime Minister Barnier’s political ending last December.

There is a technical difference in that Barnier fell to a no-confidence vote following his use of Article 49.3 to try and push through his budget, while Bayrou has opted for the (even) less likely to succeed confidence vote under Article 49.1, in which abstentions will be excluded rather than count towards the government tally.

However, the outcome is almost certain to be the same. With all the major opposition parties indicating they will vote against, Bayrou’s government too is expected to fall. This was always likely to happen after Bayrou published his proposed budget consolidation, a sensible plan economically, but politically self-destructive.

At first sight, it may appear odd that Bayrou has opted for the faster exit of a confidence vote now, rather than a no-confidence vote later in the year when the budget needed to be passed; but perhaps he hoped to leave time to adjust the budget if necessary, or perhaps he wishes to highlight how the opposition parties are being fiscally irresponsible.

If the confidence vote fails, President Macron will face the same choices he did at the end of last year, with the additional possibility of dissolving parliament and calling a fresh election. Macron is still very unlikely to resign before his term ends in 2027, seeing himself as the key defender of France against populist forces. He could appoint a new prime minister from the centrist parties (Defence Minister Sébastien Lecornu would be a favourite) or try to appoint a prime minister from the centre-left (such as former Prime Minister Bernard Cazeneuve).

Either way, such a government would still face the reality of a deeply divided parliament and would struggle to form a majority capable of passing a budget, so such a government might also be very short-lived. Longer term, an ongoing series of failed centrist governments would make the chances of a renewed centrist victory in 2027 elections less likely.

That leaves the prospect of a fresh legislative election as the riskier but more likely option for President Macron. Rather than repeating a twice-failed strategy, Macron can gamble on the hope that enough of the electorate accept the need for sensible fiscal consolidation and improve the centrist parties’ position in a new parliament.

This would be a genuine gamble. Opinion polls are scarce in France outside election season, and the two-stage process makes accurate predictions difficult. Opinion polls before the 2024 elections pointed to a far-right Rassemblement National (RN) victory, but in the end they came third behind the broad left-wing Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) coalition and the centrist Ensemble alliance. One key question is whether the NFP coalition – ranging from far-left La France Insoumise (LFI), through Communists and Greens to the centre-left Socialists – can successfully run a united campaign again. There are four plausible outcomes.

- Another hung parliament, perhaps with more RN seats. President Macron would be no worse off than before and would try to find a Prime Minister who can command a temporary majority. No successful fiscal consolidation likely.

- An RN victory. President Macron has no choice but to appoint RN leader Jordan Bardella as Prime Minister, which would leave Macron with the presidential responsibility for foreign (and EU) affairs, with Bardella having prime ministerial control over domestic policy, with some constraints. This would be awkward given the only things they agree on are increased defence spending and keeping LFI out of power. French budget deficits would likely worsen, bringing a fiscal crisis closer.

- An NFP victory. President Macron would have to appoint the candidate of the left-wing parties. This would make a fiscal crisis very likely. It would also set up RN as the face of change into the 2027 elections, making an RN victory in both presidential and parliamentary elections more likely.

- An Ensemble victory, possibly with support from other parties on the centre-right or less likely centre-left. President Macron could appoint his choice of prime minister, and fiscal consolidation could take place. This is the least likely of the four plausible outcomes, and the only outcome of the four that would be expected to lead to a reduction in French risk over the next year.

Moody’s downgraded France to Aa3 last December and currently sees a stable outlook1. S&P and Fitch have rated France AA- for longer, and both agencies have a negative outlook2 and have flagged government inability to implement fiscal consolidation as the key factor. With a Fitch review due on 12 September 2025, and S&P on 28 November 2025, there is a likelihood in our view that one or both agencies downgrades France to A+ in the near term. At the margin this may lead to some selling of French bonds by foreign investors, or a reduction in demand for French bonds as acceptable collateral.

Looking ahead to the 2027 presidential election, it seems likely that the RN candidate will go through to the second round. Whether that is Bardella or Marine Le Pen depends on the outcome of her appeal against her ban on standing for public office. Against RN is less certain, as French presidential contests can throw up significant surprises, such as Macron himself in 2017. The current favourite is former Prime Minister Edouard Philippe, now head of the centre-right Horizons party, but other plausible candidates include former Prime Minister Gabriel Attal (Ensemble, and Macron’s natural political heir), Bruno Retailleau (leader of centre-right Les Républicains, or LR), and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (leader of LFI).

Opinion polling for most of those potential run-offs stands very close to 50-50, apart from for Mélenchon, who looks set to lose to Bardella or Le Pen. Legislative elections that follow are more likely to lead to a working presidential majority. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to see any meaningful turnaround for France before this.

Whether the trigger is a political event, a ratings downgrade, contagion from elsewhere, or something else, as highlighted in our recent research paper on fiscal sustainability, we see France as on an unsustainable trajectory that will lead to a fiscal crisis, potentially broadening out into a second eurozone sovereign crisis.

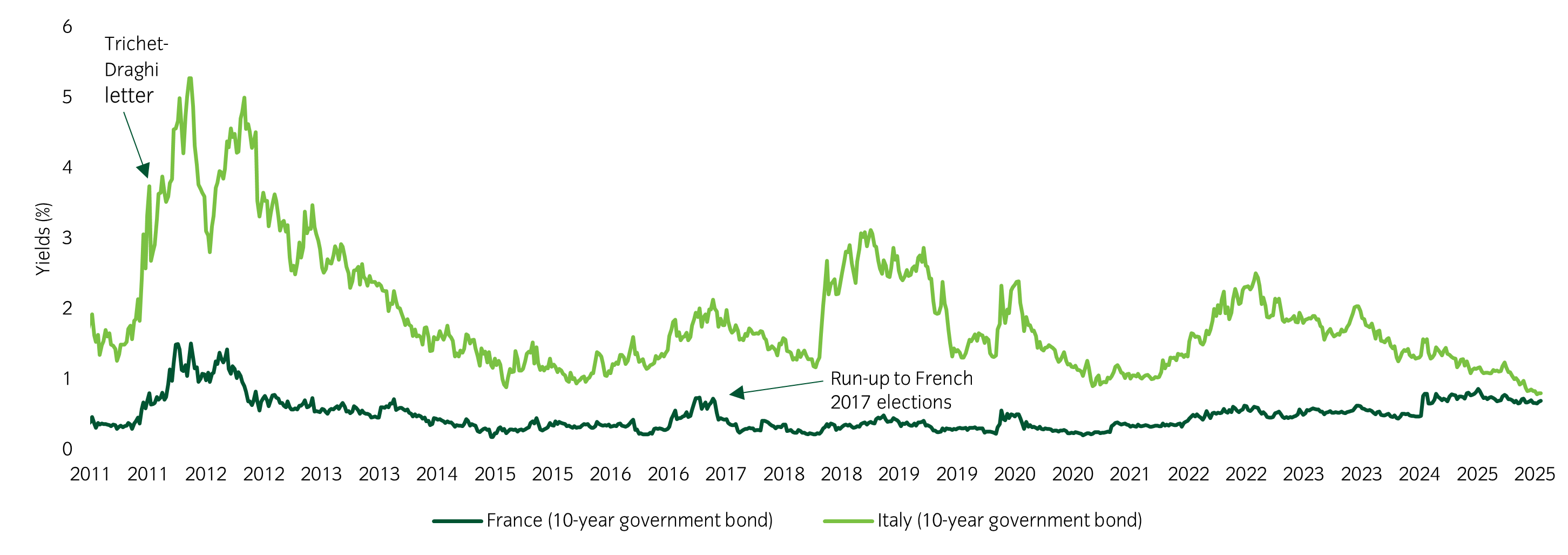

The European Central Bank (ECB) has improved tools to deal with such a crisis, but it is not clear that they would be used quickly if the problem is one of France’s own making. It is quite possible to imagine a future letter from ECB president Christine Lagarde to Prime Minister (or President) Bardella, setting out what the French government needs to do before ECB support is made available, similar to the letter from Jean-Claude Trichet and Mario Draghi to Berlusconi in 2011. France is highly unlikely to default, but French spreads could go significantly wider if a crisis hits.

Figure 1: French government bond yields are nearing Italian yields