Executive summary

- Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi led the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to a historic lower‑house supermajority in the February 2026 election, restoring legislative decisiveness and reopening the long‑stalled debate on constitutional revision focused on defence.

- A faster pace of Japanese rearmament and a stronger defence posture within a rules‑based order will likely be welcomed by the US and most regional partners but could increase tensions with China and North Korea.

- A more supportive fiscal stance, anchored by a credible commitment to debt sustainability, could make the near‑term rise in deficits less concerning than initially feared.

- We would expect the following market implications.

- A firmer yen over the medium term

- Continued outperformance of Japanese equities, especially domestically oriented and defence‑linked sectors, assuming a sustained recovery in capex

- The Bank of Japan to continue normalising policy rates

- The outlook for longer‑dated Japanese government bonds remains nuanced, reflecting a volatile balance between the risks of increased issuance and the possibility of savings repatriation

A new era for Japanese politics

In February 2026, just four months into her premiership, Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, Japan’s first female leader, led the LDP to a historic supermajority. The party won 316 seats, surpassing past highs of 300 (LDP, 1986) and 308 (Democratic Party of Japan, 2009), and crucially breaking the 310‑seat threshold required for a two‑thirds supermajority in the lower house.

With the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) securing an additional 36 seats, the governing bloc now controls 352 of the 465 seats in the lower house, an extraordinary turnaround after the 2024 and 2025 elections, when the LDP lost its majorities in both chambers. Those defeats triggered former Prime Minister Ishiba’s resignation and ended the long‑standing LDP-Komeito coalition.

This resurgence appears driven less by a revival of support for the LDP as a party and more by Prime Minister Takaichi’s strong personal popularity, which has translated into a powerful individual mandate and substantial political capital. It remains unclear whether she will maintain the coalition arrangement with Ishin. While she does not currently need their support, the partnership may continue to offer strategic value; regardless, Ishin’s leverage over government policy has diminished.

The significance of a two‑thirds lower‑house supermajority is twofold. First, under specific constitutional procedures, it allows the government to override upper‑house vetoes, enabling Takaichi to advance most legislation despite lacking an upper‑house majority, albeit with some delays. Combined with her unusually strong standing within the LDP, it grants Takaichi far greater freedom to pursue her policy agenda than recent prime ministers have enjoyed.

Secondly, a lower‑house supermajority reopens, but does not guarantee, a path to constitutional reform. Amendments in Japan require a two‑thirds majority in both houses and approval in a national referendum, meaning any change must secure support not only across party lines but also from the broader electorate. This is particularly relevant given Takaichi has signalled her determination to put an amendment to Article 9 of the constitution, explicitly recognising the Japan Self‑Defence Forces, to a referendum as soon as possible. Ishin, should they remain part of the governing bloc, are advocating for an even more assertive revision.

The geopolitical implications of a rearmed Japan

Whether or not an amendment to Article 9 ultimately succeeds, it is clear that Japan is moving decisively toward rearmament. This will strengthen its position within Asia against a backdrop of Chinese military assertiveness, support its defence‑industrial base and allow it to deepen security partnerships.

- The United States is likely to welcome Japan taking on a greater share of regional defence responsibilities. This should strengthen the US-Japan security axis, even if it does little to alter the dynamics of the bilateral trade relationship. A clearer Japanese defence mandate will enable more advanced joint planning and interoperability, benefiting not only the US but also other regional partners including Australia, India and the Philippines.

- Prime Minister Takaichi has already provoked a strong reaction from Beijing with statements signalling potential Japanese involvement in the defence of Taiwan in the event of conflict, and the election outcome gives Takaichi a clear domestic mandate to resist Chinese pressure. Although Taiwan will likely remain the central flashpoint, Sino‑Japanese frictions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and increasingly assertive Chinese air and naval patrols are likely to intensify. For Taiwan, greater military cooperation and political support from Japan appears wholly positive. However, Japanese backing is unlikely to extend to unilateral recognition of Taiwanese independence without the US doing the same.

- Although relations with South Korea remain shaped by a difficult historical legacy, recent diplomatic signals suggest a convergence in security priorities. Prime Minister Takaichi and President Lee appear broadly aligned, and shared threats make deeper cooperation likely in areas such as missile warning, cyber defence and potentially defence‑industrial coordination. North Korea, the principal shared adversary, can be expected to respond with increased rhetoric and missile testing.

- Russia’s reaction remains uncertain. While tensions over the Kuril Islands (and possibly Sakhalin) could flare, these territories are under Russian control, and Moscow’s strategic focus is currently directed elsewhere.

Overall, Japan’s renewed confidence in its defence posture will likely heighten tensions with China and North Korea, but it will also strengthen the resilience and deterrence capabilities of East Asia’s democracies. What seems most certain is that Japanese defence spending will continue to rise, with an emphasis on modern, high‑end capabilities. Japanese defence companies still have room to close the performance gap with European peers, suggesting further growth potential in the sector.

Fiscal implications

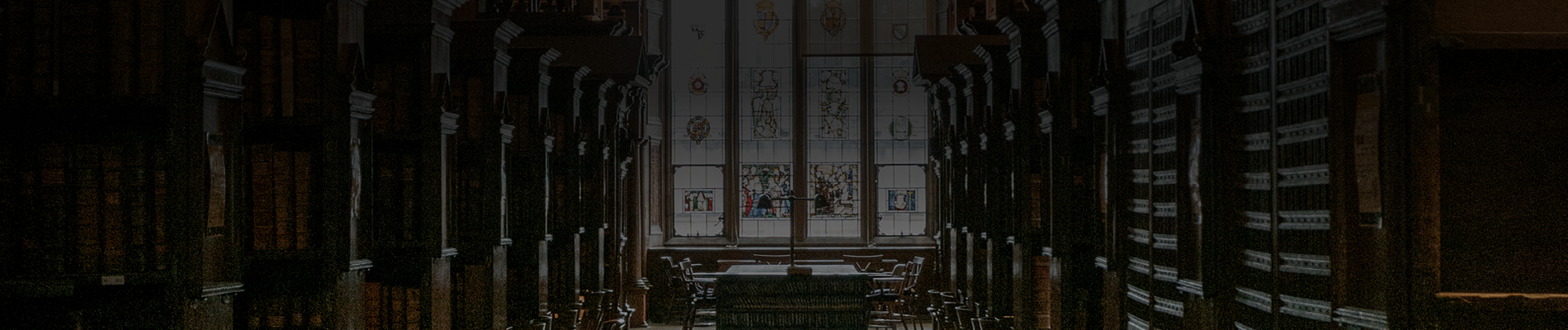

Japan’s government debt is the highest in the developed world, but its financing conditions have remained unusually stable for decades thanks to large domestic savings, a captive investor base, and the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ’s) extensive Japanese government bond holdings. These conditions have been tested in recent years as Japanese government bond yields rose following the BoJ’s removal of yield‑curve control and the gradual normalisation of policy rates. Even so, the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been drifting lower, helped by the return of inflation and the slow pass‑through of higher rates; with an average maturity of 8.6 years, Japan’s debt stock only reprices gradually.

Figure 1: Japanese debt/GDP peaked in 2020 and is projected to decline1

Ahead of the election, a proposal to cut VAT on food in response to rising rice prices unsettled markets, triggering a sharp government Japanese bond sell‑off. Takaichi, who frames her fiscal approach as disciplined and proactive rather than populist, countered by making the VAT cut temporary and reaffirming her commitment to credible debt sustainability. The government’s supermajority makes implementing the budget more straightforward and predictable, lowering the risk premium markets assign to potential policy drift.

Japan’s budget deficit is now set to widen, driven both by the new economic stimulus, which should increase the primary deficit, and by the lagged refinancing effect that pushes up interest costs. This will lead to higher government bond issuance and, all else equal, could put steepening pressure on the yield curve.

However, the government’s strong mandate for targeted stimulus and its capacity to implement policy effectively introduces the possibility of higher productivity and a positive fiscal‑multiplier effect. Well‑designed support measures, along with clearer defence spending plans, could nudge capex and wages higher at the margin. A stronger growth impulse would help narrow the output gap and reinforce inflation persistence, enabling further monetary‑policy normalisation.

In this context, credit rating agencies and long‑term asset allocators are likely to focus more on policy credibility and signs of sustained economic growth rather than on any short‑term deficit expansion. If the stimulus succeeds in durably lifting trend growth, while keeping inflation slightly above the BoJ’s target, Japan’s debt‑to‑GDP ratio could continue to drift lower over time. This is far from guaranteed, but the combination of effective governance, a supermajority that enhances execution capacity, and clear political leadership gives Japan a better prospect of achieving this than most other advanced economies. We will be closely monitoring policy implementation and Japanese capex trends to assess whether this potential is being realised.

Another factor to consider is the BoJ’s substantial holdings of equity exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and real estate investment trusts. BoJ ETF holdings are valued at roughly 14% of GDP and have periodically been discussed as a possible source of budgetary support, though heavy reliance on them would raise concerns about central‑bank independence. The BoJ is currently realising profits on these positions only very slowly, but the dividend income already helps offset interest paid on reserves and is an increasingly important stream of government revenue. If the BoJ accelerated these reductions even modestly, it would provide an additional, ongoing benefit to the government’s fiscal position.

Conclusion: market implications

In our view, the election result could have several market implications.

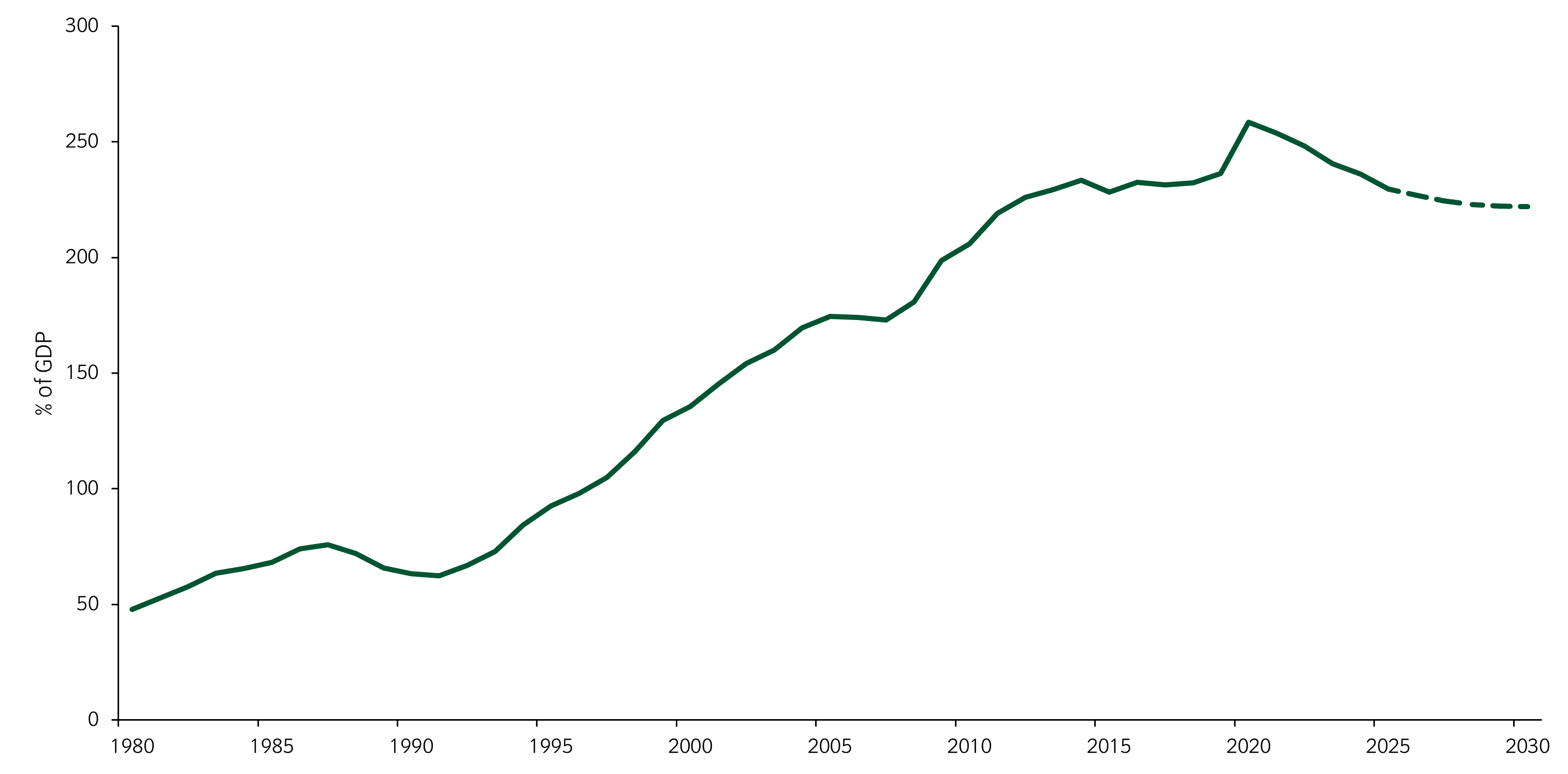

- Japanese yen: A credible domestic upswing, supported by structural reform, would be expected to draw Japanese savings back onshore. This should strengthen the yen and encourage a shift in foreign portfolios toward Japanese assets. If growth becomes more firmly established, the BoJ should be able to continue its gradual policy normalisation and may even be able to raise rates to a higher level than previously assumed. A narrower rate differential with the US and eurozone would then be expected to further boost the yen, making a medium‑ to long‑term reversal of the yen downtrend one of the clearest potential market consequences, particularly if government policy succeeds in supporting a durable pickup in capex. Periodic market worries about implementation and debt sustainability, however, are still to be expected.

Figure 2: The yen has weakened considerably over the last decade2

- Japanese equities: These should also benefit from a successful fiscal stimulus. We believe defence and defence-related sectors could benefit significantly, but a broader range of domestically oriented equities could benefit if domestic demand improves.

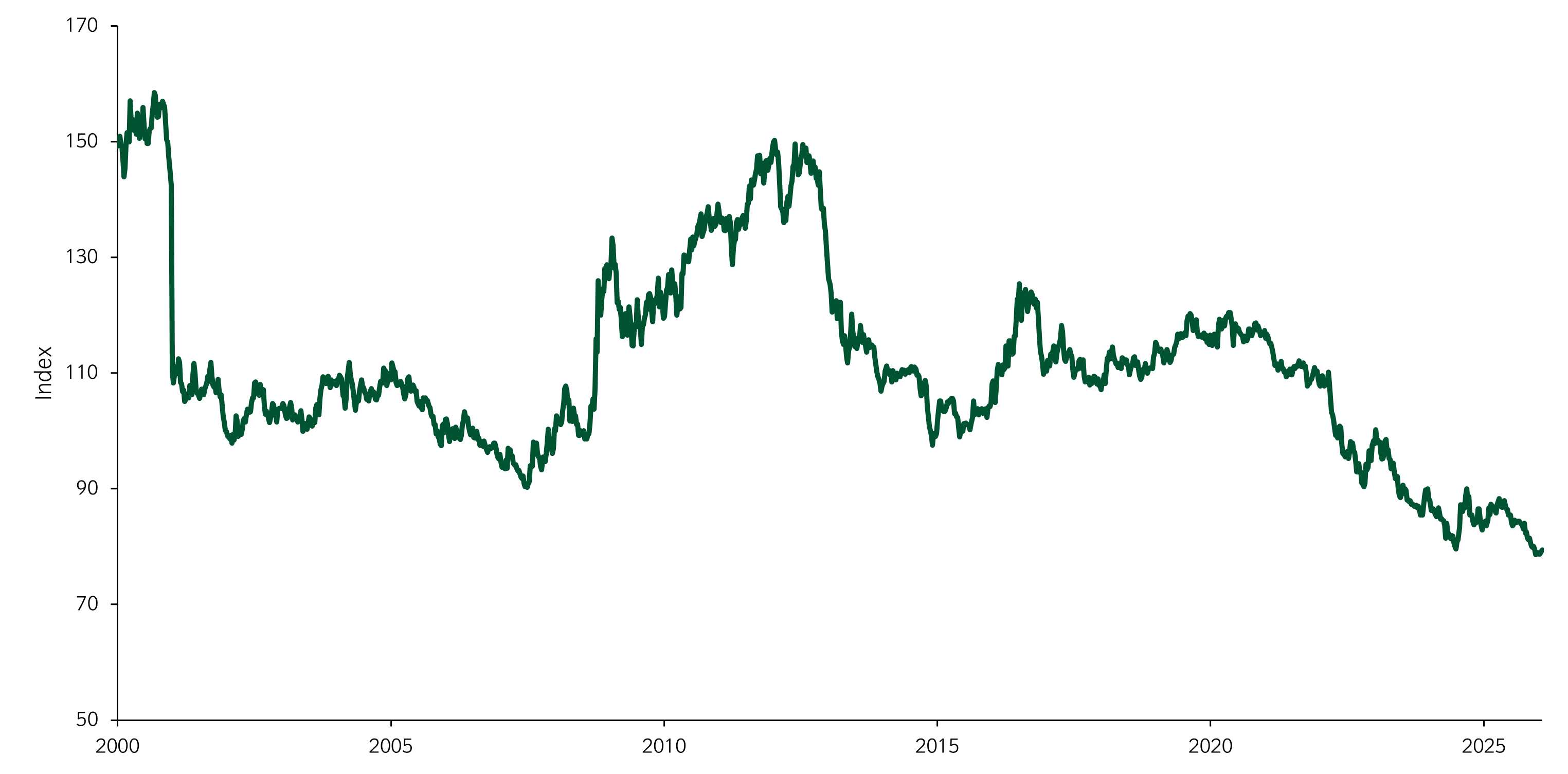

- Japanese government bonds: The outlook here appears more nuanced. Short‑dated yields should rise as the BoJ normalises rates, especially if rates are increased beyond current expectations. We may see an increase in bond issuance, but it’s unclear how much this would impact the longer end of the yield curve, which could also benefit from savings repatriation and more credible long‑term fiscal dynamics. The Ministry of Finance is acutely aware of liquidity risks at the long end and is already reducing the average maturity of new issuance, with no reason to expect any change in this position.

Japan’s yield curve is also exceptionally steep, only partly reflecting the stage of the cycle, and this could help to anchor longer-rates even in a scenario where yields at the short to intermediate area of the curve rose. For international investors, long‑dated Japanese government bonds offer attractive yields when hedged into US dollars or European currencies but are likely to remain volatile and flow‑driven.

Figure 3: 30-year Japanese government bond yields have risen significantly in recent years3

Most read

Global macro, Currency

June 2023

Global Macro Research: 30 years in currency markets

Global macro, Fixed income

October 2023

Yield-curve inversion – an unreliable recession signal?

Fixed income

February 2026

Latest fixed income review and outlook

Responsible investment, Fixed income

June 2022