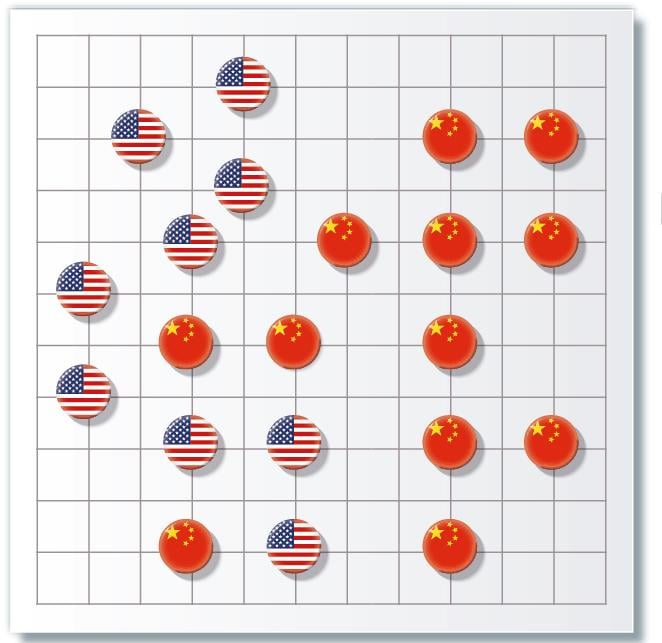

In the lead-up to the APEC summit in South Korea, trade tensions between the US and China escalated, with China imposing new export controls on rare earths and retaliating against proposed US shipping restrictions. However, Presidents Trump and Xi later agreed to extend the existing trade truce.

Key outcomes included a 10% reduction in US tariffs related to fentanyl, a one-year extension of the suspension of 24% reciprocal tariffs, and a mutual pause on implementing measures such as the US ‘Affiliates Rule’, China’s 9 October export controls, and both countries’ shipping-related actions. China also committed to resuming soybean purchases. While the past month has brought significant uncertainty for businesses and markets, the developments appear to reflect strategic positioning ahead of negotiations – ultimately, a case study in game theory.

What are they playing at?

President Trump’s approach to diplomacy often resembles a high-stakes poker game. It’s about reading the table: do you have a strong hand? Can you raise the stakes? What happens if your bluff is called – do you fold or double down? And crucially, what are the winnings in dollar terms? This mindset fosters tactical, transactional decision-making, where each interaction is treated as a game. The advantage of repeated play is learning your opponent’s patterns – when they’re likely to fold, and what signals betray a bluff. This helps explain President Trump’s emphasis on personal meetings, each aimed at securing a clear ‘win’ before swiftly moving on to the next round.

In contrast, President Xi’s strategy is more akin to weiqi – known in the West as Go. It’s a game of long-term positioning and quiet encirclement, where each move is part of a broader strategic arc to slowly shape the board. Stones are placed patiently, planning moves well into the future to gain advantage, often without the opponent realising until it’s too late.

China’s stone eye - rare earths and other minerals

China has spent years executing a patient and deliberate industrial strategy to secure dominance in the refining of a wide range of critical minerals – none more so than rare earth metals, where it also leads in mining. On 9 October, likely seeking leverage ahead of the Xi-Trump meeting, Beijing expanded its export control list to include five additional rare earth metals. It also tightened restrictions on the seven already listed since 4 April and imposed new controls on the export of technologies and machinery used in refining these materials.

This move was designed to tighten China’s strategic control over the supply chain, but also to restrict the ability to develop alternative supply chains globally.

While many critical minerals underpin a wide range of technologies, rare earths – particularly the six used in high-performance magnets – are uniquely vital to aerospace and defence applications.

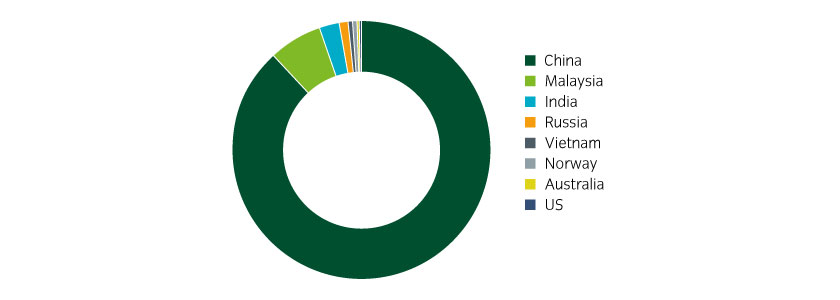

China controls around 69% of rare earth element mining production, and around 61% of those elements used for magnets. Its influence is even more pronounced in the refining stage, with roughly 88% of global processing taking place within China1. This gives Beijing substantial leverage to restrict access to these critical materials – leverage that could become existential in the event of a major conflict that saw military stocks rapidly depleted. This strategic vulnerability is precisely what makes the threat so potent, effectively calling the bluff of the US president.

Figure 1: Refined production of rare earth elements2

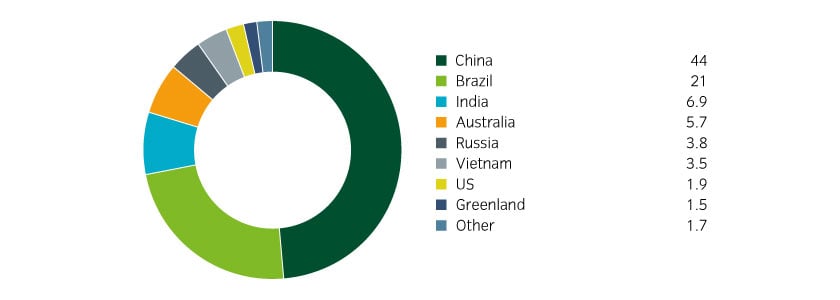

This dominance is not guaranteed to last indefinitely. The more frequently China wields the threat of restricting the supply of rare earth elements, the more urgently other nations will invest in building independent supply chains. While China holds the largest share of estimated global reserves, significant deposits also exist in the US and Australia, with potential reserves in Brazil and India (see Figure 2). These could be developed to meet Western demand and reduce strategic dependence on Chinese refining capacity.

Figure 2: Estimated reserves of rare earth metals in China are by far the largest globally (million tonnes)3

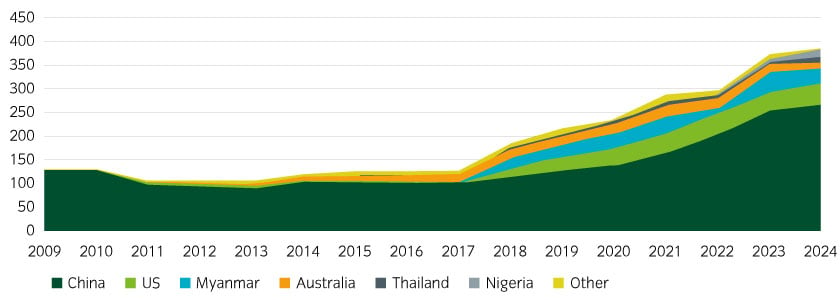

In the early 1990s, the US was the world’s second-largest producer of mined rare earth elements. However, from the late 1990s onward, China rapidly established dominance by undercutting global competitors on cost. Between 1999 and 2014, it controlled over 85% of global mining output. That share has since begun to decline, as other countries have moved to restart domestic production. It’s worth noting that Myanmar, a Chinese ally, contributes to global supply, but much of its output is still refined in China.

Figure 3: Mine production of rare earths, thousand tonnes4

A turning point came in 2010, when China temporarily halted exports to Japan during a territorial dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. In response, Japan’s metals and energy security agency, JOGMEC, invested in reviving operations at Australian miner Lynas and supported the development of processing capacity in Malaysia5.

Although China has placed restrictions on the export of relevant machinery and knowledge, the technologies used in the mining and refining of rare earth elements are broadly similar to those employed for other metals. This means that refining capacity can eventually be replicated elsewhere. Nonetheless, China is likely to retain a slight competitive edge in terms of efficiency and cost-effectiveness given its operational scale and cost minimisation.

As outlined in the 15th Five-Year Plan6, President Xi and the CCP Central Committee clearly understand that the coercive power of strategic minerals will diminish over time. Like skilled weiqi players, they are already positioning their pieces, quietly but deliberately encircling future domains of technological advantage.

America’s ace in the hole - Leading-edge semiconductors

Export restrictions are a two-way street. Since 2022, the United States has imposed controls not only on advanced semiconductor chips bound for China, but also on the machinery and software required to produce them. These rules extend beyond US firms to include foreign-made products that incorporate US technology. This reflects the deeply globalised nature of the semiconductor supply chain, with critical stages and companies based in allied nations such as the Netherlands, Japan, and Taiwan.

In response, China introduced export controls on gallium and germanium – key metals used in semiconductor wafer production – and escalated to a full export ban to the US (but not other countries) in December 2024. While China holds a near-monopoly on low-purity gallium production, the high-purity refinement needed for semiconductors also takes place in countries like Canada, Japan, Slovakia and the US. As a result, the Chinese ban has disrupted supply chains but not crippled them, prompting a reconfiguration rather than a shortage.

It is instructive to consider some of the key companies involved7.

- ASML: A Dutch company, ASML is the world’s leading manufacturer of lithography machines used in semiconductor production. While Japanese, US, and emerging Chinese firms produce deep ultraviolet (DUV) machines, ASML holds a monopoly on extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems which are essential for manufacturing cutting-edge chips at scales below 7 nanometres (nm). Under US pressure, the Dutch government revoked ASML’s export licences for EUV machines to China in 2019, though exports of less advanced DUV machines were still permitted. These restrictions were tightened further in 2024, limiting the export of more sophisticated DUV systems as well.

- Nvidia: The largest company in the world by market capitalisation at $5trn (as at 31 October 2025), Nvidia designs and sells the world’s most advanced semiconductor chips for graphic card processors and AI applications, but not to China. To comply with US export restrictions, Nvidia developed the H20 AI chip in late 2023, a 4nm processor tailored specifically for the Chinese market. Initially added to the export ban by President Trump in April 2025, the H20 was later exempted under a July agreement that allowed Nvidia to resume sales to China, with the US government receiving 15% of the revenue from those transactions. However, following a surge in H20 orders from Chinese AI firms, Beijing raised national security concerns and began promoting domestic alternatives. In response, Nvidia instructed suppliers to halt H20 production in August 2025. As Nvidia’s CEO had warned, export restrictions appear to have accelerated innovation within China’s semiconductor ecosystem rather than stifling it. Notably, the latest Trump-Xi meeting did not include any discussion of lifting restrictions on Nvidia’s most powerful Blackwell chips, contrary to some expectations.

- Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC): TSMC is the world’s leading fabricator of advanced semiconductor chips, producing at cutting-edge scales of 3nm and even 2nm. It plays an outsized role in Taiwan’s economy, contributing nearly 25% of GDP, and serves as a critical supplier to global tech giants. While new fabricator plants are being developed in the US, Germany, and Japan through subsidiaries and joint ventures, Taiwan remains the core of its operations. Competitors such as Samsung (South Korea), GlobalFoundries (Singapore), and various European and Chinese firms also contribute to global chip production, but none match TSMC’s scale or technological leadership. As a result, Taiwan represents a vital node in the global semiconductor supply chain – one with profound strategic implications for both military and economic security. President Xi has repeatedly stated his intention to see Taiwan reunified with mainland China, and any disruption to TSMC’s output would severely impact US military resupply capabilities, given current dependencies. Thus, while Taiwan remains a key flashpoint in US-China tensions, the mutual reliance on advanced chip production acts as a powerful deterrent to outright conflict, at least until alternative fabrication capacity is fully established elsewhere.

- Huawei and SMIC: These companies are leading Chinese competitors to Nvidia and TSMC respectively. Despite only having access to older DUV lithography machines, they have been able to produce 7nm chips since 2023 and have pilot produced 5nm chips, though at lower efficiency and greater cost than TSMC equivalents. At present SMIC chips are roughly three to four years behind TSMC, but strong government backing has led to ongoing innovation even without access to EUV lithography and could lead to improvements in scale and economics over time.

Conclusions - tactical versus strategic outlook

For now, both China and the US have a tactical interest in maintaining access to critical supplies such as rare earths and semiconductors. China’s ability to push back against US pressure has grown significantly since President Trump’s first term, and his instinct to escalate ahead of negotiations risks unintended consequences. Strategically, the two powers remain locked in a second Cold War, competing for dominance over global governance systems, despite their deeply integrated economies and overlapping interests in areas like climate, energy and financial stability.

We should expect periodic, unpredictable flare-ups in trade tensions and embargo threats that will rattle markets. These episodes are likely to be followed by de-escalations, at least until one side secures control over a key pressure point without exposing its own vulnerabilities. It’s a long game and at present, China appears better positioned. For the US, the priority should shift from tactical wins to rebuilding a coherent long-term strategy.