Executive summary

- On January 3, 2026, US special forces executed a rapid strike in Caracas, capturing Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife within 30 minutes.

- The US government said the operation was based on their interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine under the “Trump Corollary,” with potential ripple effects for Cuba, Iran, and others. If successful, this approach could become a blueprint for US actions against other regimes in the Americas and beyond.

- Spheres of influence are replacing universal values, if the US steps away, it could allow China to eventually engineer a peaceful reunification with Taiwan.

- Colombia could be a major beneficiary of this US policy shift towards Venezuela. Reshuffling Venezuela’s geopolitical stance without an outright regime change reduces refugee risk and eliminates safe havens for ELN guerrillas, strengthening Colombian security. Economic reopening could restore trade flows, improving Colombia’s current account and reinforcing its role as Washington’s most reliable ally in Latin America.

Regime change in Venezuela

In the early hours of 3 January 2026, more than 150 aircraft neutralised Venezuelan air defences while elite Delta Force and 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) operatives stormed Venezuelan President Maduro’s Caracas compound, capturing him and his wife within 30 minutes. Both were swiftly extracted to a US naval vessel and flown to New York to face charges of narco-terrorism and money laundering.

It is worth noting that the capture of President Maduro by US special forces and his transfer to the United States to face drug charges is not without precedent. Thirty-six years ago, after a five-day invasion of Panama and a ten-day standoff – during which US forces famously blasted rock music outside the Vatican embassy where Panamanian ruler and former US ally Manuel Noriega had sought refuge – Noriega surrendered on January 3rd. He was taken to the United States to stand trial for drug trafficking and money laundering.

Although classified as a prisoner of war, Noriega was convicted, imprisoned, and later extradited to France two decades later. Maduro’s capture simply compresses that precedent into a single operation. From a legal perspective, it is no more or less defensible under international law than the Panama invasion or similar actions before and since. History shows that great powers have always acted this way when they believed they could.

Why Venezuela is important

Venezuela’s ties with China and Russia have strengthened markedly in recent years, anchored by deep economic and military cooperation. Yet the reality behind those ties is more nuanced. China remains Venezuela’s largest oil customer and principal creditor, and in 2023 the two countries elevated their relationship to an “all‑weather strategic partnership.” However, Beijing has steadily reduced its exposure to Venezuela since 2015, constrained by the collapse in global oil prices, operating challenges in an unpredictable legal environment, and weaker personal ties between President Maduro and China’s leadership compared with the Chávez era. Today, Venezuela accounts for only a marginal share of China’s crude imports, and its heavy, low‑quality barrels play a negligible role in China’s energy mix.

Russia, meanwhile, has maintained strong rhetoric but has been unable to offer substantive support since its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. While Moscow remains Venezuela’s primary defence partner – having supplied more than $14 billion in military equipment since 2001 and seeking to maintain a strategic presence in the Western Hemisphere – its practical ability to assist has diminished significantly.

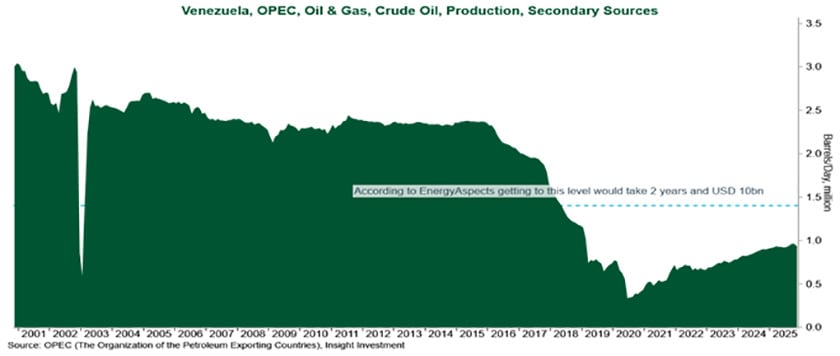

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves to the amount of approximately 300 billion barrels of oil, larger than Saudi Arabia, and sizeable deposits of gold, diamonds, iron ore and bauxite. Government-linked assessments also point to as much as 300,000 tonnes of rare earth elements – although the ability or viability of their exploitation is more a derivative of industrial processes than probable reserves. However, huge amounts of investment would be needed to tap these resources. For example, it would take an estimated two years and $10bn of investment to increase oil production by 500,000 barrels/day, about a third of the way back to levels prevalent 10 to 20 years ago.

Figure 1: Increase Venezuelan oil production would take time1

Whether Venezuela secures the investment it needs – and sees US sanctions lifted – will depend on how pragmatic Interim President Rodríguez proves to be. While her tone has been combative for domestic audiences, which may be necessary to consolidate power, she seems to be cooperating thoroughly with the US. The US has already warned of further military action if Caracas resists cooperation. This will not be necessary. Rodriguez has been the long- time interlocutor with US policymakers and industry. This cooperation includes redirecting oil exports to the US rather than Cuba. A more defiant position could see US action intensify, which could have costs for both Venezuela and the US.

Implications for other countries

US actions against Venezuela align closely with the revised National Security Strategy published in November. What is new is the speed and force with which Washington has implemented these measures, signalling broader implications for US policy toward other nations. President Trump has actively promoted what he calls the “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, explicitly naming countries that should take notice. If Maduro’s capture succeeds in reshaping the regime’s behaviour without a full-scale invasion, it could serve as a blueprint for how the administration intends to confront other governments in Latin America, and potentially beyond.

- Cuba: Remains heavily reliant on Venezuelan oil and continues to be a longstanding ideological adversary of the United States. Washington appears confident that cutting off Cuba’s oil supplies will eventually trigger the Cuban regime’s collapse. However, if that strategy fails, the prospect of more direct action could resurface – particularly with Cuban-American Secretary of State Rubio influencing President Trump. In that scenario, the temptation to “reverse the Bay of Pigs” may stay firmly on the agenda, potentially within a two- to three-year horizon.

- Iran: President Trump has explicitly warn that Tehran will face consequences if protesters are harmed. Washington has already demonstrated its willingness to use airstrikes to influence Iranian behaviour, but if those efforts have failed in areas the administration prioritizes, further military action remains possible. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu will likely work hard to keep Iran high on Trump’s agenda. That said, the new National Security Strategy places the Middle East only fourth in priority –behind the Americas, Asia, and Europe.

- Greenland: Although global warming should ease access to Greenland’s valuable rare earth minerals, the US’s priority appears to be the country’s strategic value for missile detection and sea-lane monitoring. Unlike Venezuela, Greenland is not a hostile regime; it is a self-governing territory of NATO ally Denmark, and the US already operates a major base in the country at Pituffik. If Washington wanted additional bases, this could likely be negotiated without coercion. However, Trump appears to view Greenland as part of the Americas, consistent with his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, and sees Danish sovereignty as an anachronism. Given Denmark’s decades of underinvestment in defence, any US move to assert control would face minimal resistance – similar to Russia’s swift takeover of Crimea in 2014. NATO allies would offer words, not force, as they remain dependent on US support against Russia. For Denmark and Greenland, the rational course may be to negotiate, even while signalling opposition. A peaceful transfer of sovereignty within the next three years is increasingly plausible – echoing the 1917 sale of the Virgin Islands from Denmark to the US. President Trump may well view this as key to his legacy.

Could other powers adopt similar tactics in their own spheres of influence? The real precedent here is the abduction of a foreign leader without a full-scale war. Russia hasn’t used this in its hybrid warfare playbook yet, but it’s conceivable in the “near abroad” under the guise of protecting Russian speakers – though likely not against NATO states or Ukraine for now. For China, the implications are twofold: first, Trump’s approach creates an opening for Beijing to present itself as a more rational partner in Latin America, strengthening its influence there. Second, Trump’s embrace of spheres of influence could pave the way for a grand bargain where China limits its reach in the Americas in exchange for US acceptance of Taiwan as part of China’s sphere. If Washington signals it won’t defend Taiwan, Beijing may achieve reunification through pressure rather than invasion, relying on the credible threat of force rather than actual conflict.

Colombia could be the winner from this action

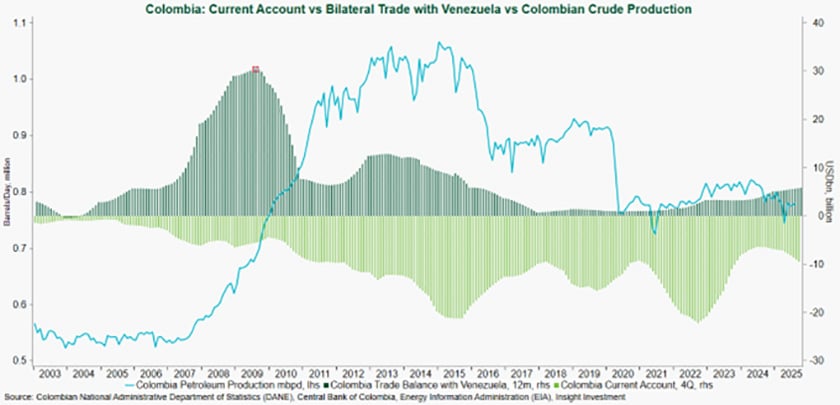

The reopening of Venezuela’s economy and the return to growth will provide a significant boost to Colombia. Currently, Colombia exports only one-sixth of the goods it once sold to Venezuela at the peak of bilateral trade, and its trade surplus has shrunk from $30bn to just $5bn (see Figure 2). This collapse in trade is a key driver of Colombia’s current account deterioration over the past decade, despite a surge in Colombian oil production in the 2010s.

Figure 2: Colombia current account vs bilateral trade with Venezuela2

Meanwhile, the risk of civil war or a disorderly collapse of the Venezuelan regime has eased for now, reducing the likelihood of a sudden humanitarian crisis spilling across the border – a scenario that would have imposed a large, though hard-to-quantify, fiscal burden on Colombia.

Colombia remains the United States’ most important ally in Latin America, with its stability and cooperation critical to US operations in the Caribbean and anti-narcotics efforts. This partnership has remained strong and unwavering under President Petro. Policy, security, and commercial elites in Colombia are deeply interconnected, and US objectives – such as maintaining state stability, promoting a market economy, and combating drug trafficking – align closely with the priorities of Colombia’s elite. This alignment was evident in 2025 when US threats to withdraw certain benefits or cooperation frameworks were quickly reversed, as such measures would have risked strengthening guerrilla groups and cartels.

In stark contrast, Venezuela has become a pariah state, isolated diplomatically and excluded from numerous regional institutions, while maintaining ties only with a handful of rogue allies. Latin American countries that sought to preserve orderly relations with Venezuela – such as Brazil and Colombia – did so out of necessity, as regime instability threatened to unleash millions of refugees. Even left-leaning governments condemned Maduro and refused to recognize his legitimacy; Chile’s Boric and Bachelet, for example, issued strong denunciations. Such consensus for the removal of any other Latin American leader would be unthinkable, yet in Maduro’s case, there is near-universal relief at his departure.

For Colombia, the collapse of Maduro’s regime offers a strategic advantage: the elimination of Venezuelan safe havens for the ELN, the last significant leftist guerrilla group opposing the Colombian state. ELN’s survival depended on sanctuary in Venezuela, but recent reports suggest its fighters are fleeing following Maduro’s capture and the purge of Cuban operatives. While some FARC remnants have resumed activity inside Colombia, they now function purely as criminal organizations – a critical distinction, as they no longer enjoy the international recognition that once constrained Colombia’s response.